Carbon credits offer an opportunity to unlock climate finance for the African continent. But the region currently accounts for just 2% of trading on the global carbon markets valued at over $2 billion.

Demand for carbon credits is expected to increase by a factor of 15 or more and could be worth over $50 billion by 2030. But the current market is fragmented and complex. High-quality carbon credits are scarce because accounting and verification methodologies vary and pricing data remains limited.

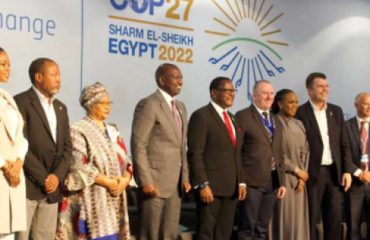

The Africa Carbon Market Initiative, or ACMI, which was launched during last year’s United Nations Climate Change Conference, aims to rapidly increase the production of African carbon credits while ensuring that revenues are transparent, equitable, and create jobs.

According to Sherif Ayoub, the senior director and focal point person at the initiative, ACMI aims to promote carbon trading and help groups develop the skills they need to navigate the various barriers to trading. The initiative wants to mobilize up to $6 billion by 2030 and more than $100 billion per annum by 2050 as well as create 30 million jobs by 2030 and more than 100 million jobs by 2050.

But in order to achieve this, Ayoub said integrity has to be central to the initiatives’ mission. There are global concerns about the integrity of Voluntary Carbon Markets, or VCMs, with lingering questions about transparency, equity, and effectiveness.

Lindsay Smith, the natural carbon capture project lead at the Global Strategic Communications Network, said rules governing VCMs have been unable to prove that some projects have carbon removal benefits.

The AMCI road map also highlights the need for increased transparency on the share of revenue received by communities. The amount of money that trickles down to communities from these climate projects remains shrouded in mystery. Nine out of 10 intermediaries driving the carbon trading system do not disclose their fees or profit margins, according to a study by Carbon Market Watch.

“Intermediaries have a role to play in the voluntary carbon market because they connect those with money to those who need it. But today, these speculators are reselling credits at sometimes several times the price they paid for them,” the study found.

Susan Chomba, the director of vital landscapes for Africa at the World Resources Institute, said currently intermediaries are siphoning benefits from communities on the front lines of climate change.

“It is very expensive when speculators run carbon projects without involving local communities. [Communities] should be involved in negotiating benefit sharing to ensure they do not get the short end of the stick,” Chomba said.

Communities need to be trained on how the verification process works as this would reduce the cost of monitoring, reporting, and verifying carbon markets, she added.

Ayoub said ACMI is in the process of establishing activation programs in Kenya, Nigeria, Ghana, and Rwanda, which should be launched next month. The programs will support countries to develop guidelines based on contextual realities and projects that benefit communities. The initiative also plans on publicizing its Advanced Market Commitments to ensure that developers reveal their profit margins and percentages that will be paid to communities, he said.

Chomba said another way to ensure communities benefit would be having systems that reward them for caring for natural assets before the value of their forests or other carbon-absorbing resources can be traded on the VCMs. For instance, governments that have banned entry into forests could allow communities living along them to grow food crops within the forests while also caring for the trees, she said.

Governments could also introduce a carbon tax, where big emitters pay a levy that can be used to support communities living side by side with natural assets, while also eliminating corruption from the market, Chomba said.

James Mwangi, the founder of Climate Action Platform for Africa, said communities that protect natural resources need to start receiving financial compensation.

“When I worked as a consultant, no one assured me of the intangible value of my work by shaking my hand and thanking me. I received a cheque which allowed me to pay for my family’s expenses. The people living on the edges of forests should also receive value for the work they are doing,” he said.