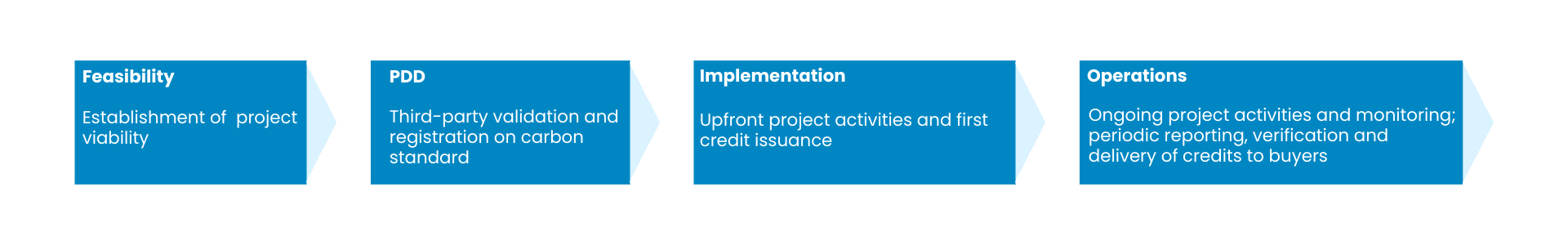

In understanding how to finance carbon projects, it is important to have an overview of the project development process because capital raising needs and available instruments vary across stages of the project development cycle.

At a high level, carbon projects go through 4 phases: Feasibility, Project Design Document (PDD), Implementation, and Operations. An overview of key players involved in the process is expanded upon in the Introduction to Carbon Markets in Africa page.

Feasibility: project developer undertakes pre-feasibility and feasibility studies to understand carbon and non-carbon impact potential of the project, assess government and community receptiveness, and determine financial viability.

PDD: project developer creates Project Design Document (PDD), which outlines the details of the project, including planned activities, expected impact, and monitoring and reporting plan. The developer submits the PDD for third-party validation of future carbon credits and for registration of the project and its expected credit generation on carbon standard.

While exact scope and timeline of activities vary across sectors and project sizes, the feasibility and PDD phases can take anywhere from 1-3 years to complete and require US$200K-US$1M. These costs can be attributed to contracting experts that develop the feasibility studies or PDDs, paying for third-party validation and registration, establishing a pilot technology (such as a DAC prototype), and developing core development activities such as stakeholder engagement and permit acquisition.

Implementation: project developer and/or proponent undertakes project activities according to the PDD. Project developer engages in Monitoring, Reporting and Verification (MRV) of the carbon impact and issues carbon credits, also referred to as Verified Carbon Units (VCUs) following third-party verification.

Operations: Project developer continues issuing and selling VCUs and manages operations and associated risks over the lifetime of the project.

Note: While exact scope and timeline of activities vary across sectors and project sizes, the feasibility and PDD phases can take anywhere from 1-3 years to complete and require US$200K-US$1M. These costs can be attributed to contracting experts that develop the feasibility studies or PDDs, paying for third-party validation and registration, establishing a pilot technology (such as a DAC prototype), and developing core development activities such as stakeholder engagement and permit acquisition.

Sources and/or additional resources:

Carbon finance is the collection of investment mechanisms available to fund carbon projects, and more commonly refers to the use of capital committed or provided upfront by a carbon credit buyer (or offtaker) in return for carbon credits.

Historically, financing climate initiatives has been largely driven by government and philanthropic capital. However, according to the Climate Policy Initiative, Africa will need US$2.8 Trillion between 2020 and 2030 to implement its Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), which are commitments made by countries under the Paris Agreement, outlining their climate action plans and targets to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Carbon finance has the potential to help fill the financing gap that philanthropic and traditional forms of capital cannot do on their own. Carbon projects’ long payback periods, less certain cashflows given varying carbon price projections, and project execution complexity are examples of why carbon projects may not match the expected returns and typical terms of traditional investors such as banks and private equity funds. On the other hand, carbon finance is driven by a new source of capital - the budgets associated with corporate and government commitments to offset GHG emissions.

Credit trading mechanisms were first established in the 1997 Kyoto Protocol. Now, the Kyoto Protocol has been replaced by Voluntary Carbon Markets (VCM), compliance markets, and Article 6 within the 2015 Paris Agreement (please see here for more details within our Introduction to Carbon Markets in Africa page). This page will focus on financing for carbon projects primarily through the VCM, as it is the most common mechanism for African carbon projects to access financing today – however, we anticipate that compliance markets and Article 6 (with enhanced clarity as to how that market will work in subsequent COP meetings) will play a more significant role in the future. Additional detail on compliance markets can be found in the Introduction to Carbon Markets in Africa page.

Latest on Article 6

Article 6 of the Paris Agreement provides a mechanism for the trading of emissions reductions between countries. Article 6 creates a framework that allows countries to deploy capital or to require companies to deploy capital into carbon credit purchases, which can create another avenue for selling carbon credits in addition to compliance and voluntary markets.

Approximately 69 bilateral agreements have been signed under Article 6, according to data compiled by S&P Global Commodity Insights and the UN Environment Programme. However, the first deal to successfully close only concluded in January 2024 between Switzerland and Thai company Energy Absolute Public Co. Ltd. for the Bangkok E-Bus Program. Therefore, developers should follow closely the evolution of local frameworks in the host country of their carbon projects.

Article 6.2 stipulates that once a credit is sold, the host country of the project must take a Corresponding Adjustment (CA) to ensure that the country is not double counting that credit by counting it toward their own NDC, which is expected to have implications on both compliance and voluntary markets.

However, there is currently no mechanism or infrastructure for issuing and tracking correspondingly adjusted credits within the voluntary markets. That said, correspondingly adjusted credits are expected to have higher prices due to a growing perception among investors and carbon credit buyers that these types of credits are a marker of quality and have lower risk of expropriation from the host government. More information and resources on Article 6 can be found in the Introduction to Carbon Markets in Africa page.

Sources and/or additional resources:

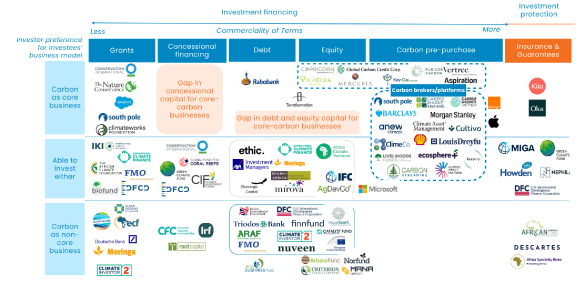

Financing for carbon projects today is made up of a varied ecosystem of capital providers, ranging from equity investments to pre-purchase offtake agreements, and completely concessional to commercial return expectations. The availability of carbon finance is fast growing but remains low as the ecosystem is still nascent.

A project’s ability to raise capital depends on its financial viability and the returns it is expected to generate. Investors’ expected returns vary across investor types and based on the risk profile of the project, which depends on the stage in the project development lifecycle and the developer’s track record, among other factors. For example, credit buyers mainly focus on the projected price of carbon credits and typically target 20+% IRR (Internal Rate of Return) on projects developed by first-time developers in African markets.

The earlier the project is in its lifecycle, the higher the actual risk and perceived risk by an investor. Therefore, at the feasibility stage, the financing mechanisms available mostly include grants and concessional capital. Some project developers may have raised company-level financing and use it to cover initial project development costs.

When a developer completes feasibility studies, demonstrates traction and potentially signs agreements with key stakeholders like the government or local communities, and finalizes PDD, the project becomes less risky and the pool of available capital providers becomes wider. The different investment mechanisms and mappings of capital providers are elaborated on in sections 5 and 10 below.

It should be noted that there are limits to the use of carbon projects and carbon finance to create climate and other co-benefit impacts (e.g., water quality, soil health, community benefits, biodiversity). Because there is a high upfront cost to establishing a carbon project with a major standard setter like Verra or Gold Standard, small-scale projects will find it difficult to achieve financial feasibility.

Sources and/or additional resources:

Generally, there are three types of projects with differing capital needs. These include the following:

Each of these archetypes have different cashflow profiles and company/project structures that make capital raising different.

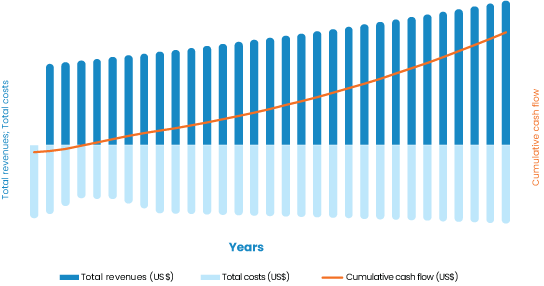

A capital-light business model for avoided emissions, such as a nature-based avoided deforestation (REDD+) project, has lower upfront capital requirements and a more consistent set of carbon credits issued over time. These projects can generally raise capital once at the outset to cover all project costs and are sometimes able to cover much of this through grants. Some conservation projects that have traditionally relied on non-carbon revenues and/or philanthropic funding have started to monetize carbon credits as an additional source of revenue to improve the long-term financial sustainability of these projects.

African Parks, which manages 22 areas covering 22 million hectares across 12 countries, started issuing REDD credits to boost revenues. African Parks started issuing credits for the first time towards the end of 2023, across two REDD projects – the Chinko conservation project in the Central African Republic and the Pendjari and W-Benin National Parks in Benin.

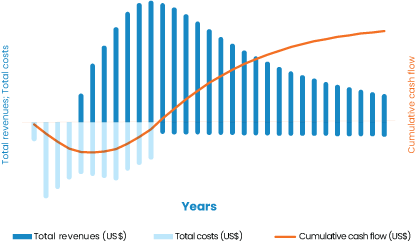

An upfront capital-intensive business model such as reforestation, Direct Air Capture (DAC) or biochar will need to raise much more significant upfront capital, likely in several phases with different types of investors and credit offtakers.

Founded in 2022, Octavia Carbon is one of Africa’s first DAC companies. As announced in 2024, Octavia Carbon received funding from impact investor Renew Capital and signed a pre-purchase agreement for 950 tonnes with Danish carbon removal platform Klimate (more on pre-purchase agreement in the next section). Octavia Carbon will use the funding to develop the technology and scale their production capacity.

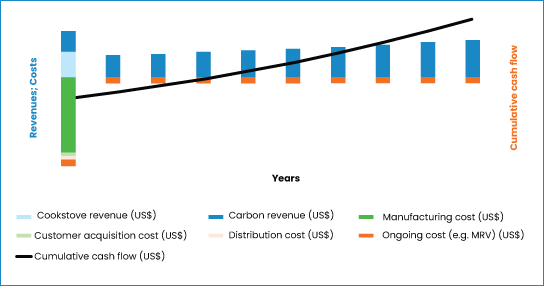

For archetype 3, a company or project may have alternative, more traditional revenue streams (e.g., the sale of a product like a cookstove) and therefore can raise from a wider set of investors. In archetype 3, where carbon credits are used to reduce the price of a product, the company must cover the upfront cost of these and recover the cost over time as credits are issued.

Founded in 2014, Koko Networks has raised over $100M in carbon finance. Carbon credits are used to significantly subsidize the cost of the stove and fuel to make it more affordable to households. In 2022, Koko Networks raised an equity round, led by the Microsoft Climate Innovation Fund. In 2024, Koko Networks raised long-term debt from the Rand Merchant Bank of South Africa (RMB). The debt facility is securitized by the future cashflows from the company’s future carbon credit sales. Koko Networks has over 1M customers.

These three archetypes represent common projects and sectors but are not exhaustive, and often companies or projects might fall into multiple categories depending on their business model. For example, an enhanced rock weathering company or biochar company may pursue a model that is capital light or intensive, depending on the business model (e.g., whether it is a build, own and operate (BOO) model or just licensing its technology to others).

Sources and/or additional resources:

Access to capital for carbon projects varies greatly based on the developer’s core business model. The business model can be thought of as a spectrum based on how core the sale of carbon credits is to the commercial viability of the business. More diversified business models, in which carbon is non-core, can access more traditional pools of capital in addition to carbon finance (referred to as “commercial finance” below). Less diversified businesses in which carbon is the majority or sole revenue source (“core-carbon projects”) are able to access carbon finance but may struggle to access traditional pools of capital. This is primarily due to the novelty of the business model, challenge of assessing project risk, and uncertainty of demand and pricing within the voluntary carbon market.

Within carbon finance there are four main types of agreements that are commonly found defined below, with many project developers raising the capital they require and securing offtake with a combination of some of them:

Brokerage agreements: A third-party intermediary (or broker) facilitating the transaction of credits between a buyer and a seller, earning a commission on the value of credits sold

Carbon Finance Example: In 2022, Respira International signed an offtake agreement for the purchase of carbon credits from the 70,000 Ha REDD+ project implemented by Gola Rainforest Conservation Company LG (GRCLG) in Sierra Leone. GRCLG is a partnership between the government of Sierra Leone, Gola communities, the Conservation Society of Sierra Leone, and UK-registered charity Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, which led the sale of credits. The project is expected to generate nearly 500,000 credits annually through 2042.

While carbon finance is crucial to financing carbon projects, developers should understand and evaluate the trade-offs associated with these instruments, primarily the brokerage fees or discounts that buyers apply to pre-purchased carbon credits to compensate for the early-stage risk. These carbon finance agreements also include clauses defining the consequences of non-delivery of carbon credits, as well as a clear definition of events triggering these non-delivery consequences, as well as resolution mechanisms. Non-delivery triggers can include, amongst others:

Like with raising conventional financing (like debt or equity), the process to raising carbon finance can also be lengthy and take anywhere from a minimum of 3-6 months at minimum, up to 12-18 months in total – these timelines should be included within a developer’s broader carbon project development lifecycle. Financing will likely need to be raised in several stages, and some investors may only want to invest in certain cost items.

For a more in-depth explanation of commercial and catalytic finance, please refer to the Carbon Finance Playbook in the additional sources below.

Sources and/or additional resources:

Determining avenues for raising capital should be core part of the broader project development roadmap. There are several initial steps you can take to understand if and how to raise capital (including carbon finance) for your project idea.

Benefit sharing refers to a model within a project that aims to make payments to key stakeholders that play a key role in the project, including land stewards, customary land right holders and landowners (which may be Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities, or IPLCs), and local or national governments. Usually benefit sharing as a term implies a focus on IPLCs, but all stakeholders should be considered in developing a benefit sharing plan, which has significant implications on the financial model of a project. These stakeholders are critical to the success of a project and there is a moral obligation to ensure these benefit sharing agreements are structured fairly. While this might be most common and relevant to land use projects (avoided deforestation and restoration), there are considerations in any type of carbon project – for example a DAC facility being built on community land or a biochar company sourcing its biomass from smallholder farmers.

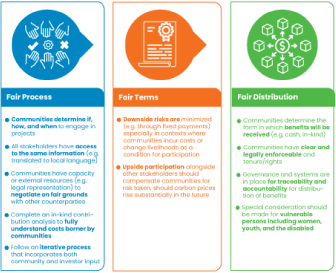

Fairness should be considered across three elements:

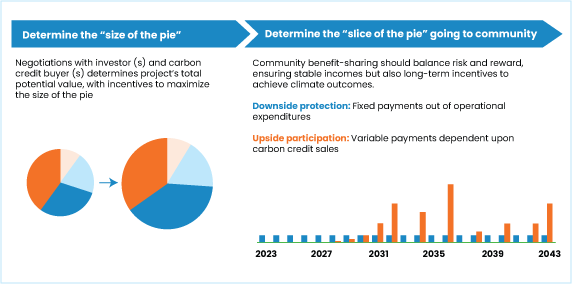

When it comes to designing a benefit sharing agreement in collaboration with stakeholders, there are two key decision points. The first is maximizing the size of the pie in negotiation with credit offtakers and the second is determining the “slice of the pie” going to different stakeholders. This is different for every project given aspects of community land ownership and project participation.

There are several more design features after determining the slice of the pie, including when and how benefits are shared with stakeholders. From a nature-based perspective, this is elaborated on in the Benefit Sharing Agreements chapter within USAID/CrossBoundary Carbon Finance Playbook linked in the additional sources below, which also includes three case studies.

Sources and/or additional resources:

Maturing and scaling the carbon ecosystem requires identifying and mitigating risks. A project’s risk informs cost and availability of capital, as lower risk projects will receive better financing terms and may have a larger pool of potential investors. A failure to mitigate risks could lead to failure of a project, which can have wide-ranging impacts on the development of a nascent voluntary carbon market. Reputational risks can be damaging by undermining the trust of investors, policymakers, and the public at large.

Projects face market-, country-, and project-level risks throughout their lifecycle, with varying degrees of impact and likelihood.

Land tenure complexity and uncertainty (applicable to land-based carbon projects)

Potential conflict with government and communities when land tenure is not clearly defined. Project delays due to time required to secure land tenure, particularly when carbon rights are tied to land rights. Risk of land expropriation and/or overriding of permits

Changes in carbon market regulations

Adverse changes to carbon markets regulations including new permitting processes, changes to accepted methodologies or jurisdictions, or higher taxes

Ambiguity around implementation of Article 6 and Corresponding Adjustments (CAs)

Inability of project to secure CA (if required or expected from investor or buyer) due to lack of agreement with host country government or lack of infrastructure in host country to provide this authorization

Expropriation of carbon rights

Expropriation-like actions of the host government preventing some or all of a project’s credits from being sold and exported. A host country may take such actions to reserve credits for use in NDCs or for sale as ITMOs

Security and political violence

Risk of civil unrest, government instability, and threat from rebel groups on project implementation and outcomes. The impact could be a delay, destruction of the asset, or full project shutdown.

Capital controls

Risk of currency inconvertibility, restrictions on capital repatriation, restrictions on investment instruments, complexity of disbursement, etc.

Foreign exchange risk

Risk of financial loss resulting from exchange rate fluctuations, particularly the depreciation of currency in which revenue is realized or the appreciation of currency in which cost is incurred.

Carbon demand uncertainty

Lower demand for carbon credits because of changes in the market, such as methodology changes or cancellations, negative perception of some project types, and changes in guidance around claims that can be made by buyers of carbon credits

Carbon price uncertainty

Lower prices for carbon credits in the voluntary market than forecasted. This could be a market-wide decline or specific to the project type, methodology, or geography.

Weak stakeholder engagement

Conflicts or failure to develop strong relationships with local communities and government stakeholders relevant for project execution. Real or perceived unfairness or failure to deliver agreed benefits to local stakeholders.

Customer risk

Risk that customer is unable to fulfill payment of offtake on delivery.

Inability to fundraise

Challenges accessing funding can cause project delays, prevent developers from accessing expertise, and in the worst-case lead to developer insolvency.

Other execution risks

Other execution risks that can cause project failure or poor performance, including poor cost management, poor design leading to high tree mortality, challenges recruiting and training staff, local partner issues, and others.

Late delivery

Failure to deliver carbon credits on the agreed date due to delays in project implementation and validation and/or verification by standards bodies.

Physical risks

Risk of fire, typhoon, and other weather-related hazards, which can cause a reversal of carbon emissions and damage project assets. Higher reversal risk requires a larger buffer pool of credits.

Other shortfall or non-delivery

Lower-than-expected issuance of credits due to factors such as inaccurate baseline carbon stocks, inaccurate project carbon stocks, project cancellation and/or invalidation, and changes in methodology

Fraud and negligence

Reduction or invalidation of carbon credits caused by fraud, neglect, or other wrongdoing on the part of the project developer.

Note: Buffer pools, insurance, the establishment of strong safeguards, and the use of technology-based Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification (MRV), can all help mitigate risks faced by carbon projects. For a more in-depth explanation of risks and mitigants for carbon projects, please refer to the Carbon Finance Playbook in the additional sources below.

Insurance is an important risk mitigation tool for large-scale projects in most industries, yet it is underutilized for carbon projects today. While insurance is common to most large-scale infrastructure projects in adjacent sectors such as renewable energy, it is not yet common for carbon projects. As the VCM scales and larger pools of more traditional capital look to fund projects, insurance will become increasingly utilized alongside other common investor protections. There are three types of risk available today:

Sources and/or additional resources:

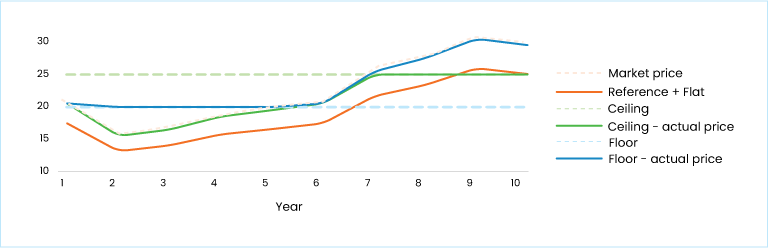

Especially within the VCM, there is no established or easily referenced market price, and beliefs about the future of carbon pricing are wide ranging. Each of these factors makes it difficult for projects to set appropriate assumptions around the price at which they will sell carbon credits, and to agree with buyers on pricing for credits that will be delivered in the future. Carbon credit prices and trends are elaborated on in our Introduction to Carbon Markets in Africa page.

Carbon credits in the VCM can be sold in the primary market through over-the-counter (OTC) bilateral sales between a carbon project developer and a credit offtaker, or in the secondary market, which can also be OTC through a broker or retailer, or on an exchange. Almost all transactions in the VCM currently happen OTC rather than through an exchange.

Within offtake contracts, there are three main ways that prices can be determined – fixed, variable, or cost-plus.

Fixed price

Fixed price contracts refer to offtake contracts where the price is agreed when the contract is signed. The price can take several forms:

Variable price

Variable price contracts place more price risk onto the seller by exposing them to carbon prices. The simplest approach uses a reference price plus a float. The reference price is an agreed benchmark that represents the market price. It can be the spot price of other credits sold from the same project, the average of broker quotes at the time of sale, or an index such as N-GEO (Nature-based Global Emissions Offset). The float price is an agreed premium or discount to the reference – for example, credits could be sold at 10% above or 10% below the reference price.

Alternatively, a floor and/or ceiling price can be used to cap downside or upside returns. Under a floor price model, the buyer would pay the maximum of the reference or floor price, and under a ceiling price model, the buyer would pay the minimum of the reference or ceiling price.

Cost-plus price

Under a cost-plus model, the carbon credit price is based only on the cost of production, plus some margin to the developer. This is most commonly used when the developer is an NGO or other organization prioritizing cost coverage, and when the project is capitalized by a single investor. In this case, the developer serves as a long-term service provider, managing operations in return for a margin. Cost-plus contracts provide downside protection for communities but no exposure to upside – a situation that can become problematic if prices rise considerably and the offtaker is selling credits in the secondary market at significant premium.

When the offtaker is selling credits onward in the secondary market, there may be opportunity for the project to negotiate an upside share, in which a portion of profits from the resale of credits is returned to the project. This model helps to ensure alignment of incentives across the life of the project, so that if prices rise considerably, the operator and communities share in this windfall.

Sources and/or additional resources:

There are several types of capital providers that range from grantors to commercial financiers, including credit offtakers providing upfront capital through pre-purchase agreements. Below is an example of one capital map focused on nature-based solutions, and other maps can be found in the additional resources below. Mapping the landscape of capital providers for carbon projects in Sub-Saharan Africa reveals the dominance of carbon finance and limited concessional capital availability. Grants are primarily provided by foundations and international NGOs but are limited in scale and can be difficult to locate and subsequent navigate the application process. Concessional financing is provided by foundations and DFIs but primarily to non-core carbon companies. Funding that is available is often not sufficient to bridge the gap to investment-readiness.

Most investors open to core-carbon business models are carbon credit buyers or brokers who will invest directly into the project, and/or into the developer in order to get preferential access to projects. Most investors willing to invest debt, equity, and mezzanine are DFIs, impact investors, and financial investors, but they tend to invest in non-core carbon companies and projects, or into the carbon project developer at the company level rather than project level.

In early 2022, AXA IM Alts – the investment manager and subsidiary of insurer AXA – and energy group ENGIE backed agroforestry start-up Shared Wood Company (SWC) through US$500M of equity and carbon credit offtake agreements. SWC will combine conservation, reforestation, and agriculture across Africa and Latin America to generate 40M credits.

Founded in 2020, Climate Asset Management (CAM) is a joint venture between HSBC and Pollination dedicated to investing in natural capital. In 2021, CAM announced the Restore Africa program, a US$150M program in partnership with the NGO EverGreening Alliance aiming to restore more than two million hectares of land and support over two million smallholder farmers over five years across six Africa countries.

Founded in 2014, BURN Manufacturing is an international cookstove company with a production facility in Kenya that has an annual production capacity of 3M cookstoves. In 2022, BURN Manufacturing received US$4M in long-term quasi equity (mezzanine investment) from the Spark+ Africa Fund, a joint venture between the investment advisor Enabling Qapital and the Netherlands-based foundation Stitching Modern Cooking (SMC). During the same year, BURN Manufacturing also received a streaming investment from Key Carbon, structured under a joint venture. In October 2023, Burn announced a US$10M green bond with proceeds used to expand manufacturing capacity and open a new factory in Nigeria.

NetZero is a French start-up pioneering large-scale biochar in tropical areas globally. In February 2023, the company raised an €11M Series A, with investors including the Stellantis Venture Fund, L’Oréal’s Fund for Nature Regeneration, and CMA CGM, a global logistics company. The company had already raised early-stage capital through 23 angel investors. In December 2023, NetZero announced a partnership with the IFC’s Upstream program, helping to build the company’s growth strategy into new agricultural supply chains in Africa.

Sources and/or additional resources: