Carbon markets are trading systems in which carbon credits are bought and sold.

By selling carbon credits, entities developing activities that remove, reduce, or avoid GHG emissions generate an additional revenue stream which improves the overall commercial viability and financial sustainability of their projects. These entities can be private project developers, companies, NGOs, governments, and other entities (The different actors and their roles are explained here).

This has the potential to attract commercial and concessional capital, making carbon markets a financial tool that can expand the pool of funding available for climate activities, which have historically relied on public and philanthropic funding. Importantly, by providing companies and their customers a financial compensation to move away from environmentally unsustainable activities or to engage in more sustainable activities, carbon markets offer a provide a financial incentive to advance climate action.

Buyers of carbon credits can be companies, individuals, or other entities, that are looking to offset GHG emissions and/or contribute to their GHG emissions reduction commitments, which can be voluntary or mandated by regulations. Examples of these commitments include companies Net Zero targets and countries’ Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs).

A carbon credit represents one metric ton of carbon dioxide or its equivalent (CO2e) that was avoided, reduced, or removed from the atmosphere, with two types of credits:

Sources and/or additional resources:

The first international carbon credit trading mechanism was established through the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) under the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, which was an international treaty that aimed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The protocol allowed high emitting countries to invest in emissions reducing projects to earn carbon credits (called CERs, or Certified Emissions Reductions). As low emitters, developing countries became active participants and suppliers of credits in the market.

There were hundreds of CDM projects that were implemented across Africa starting in the mid-2000s. South Africa, Kenya and Egypt led in the number of projects and total number of credits generated, and many projects on the continent were in sectors such as municipal waste management, small-scale hydro, reforestation, forest protection, biogas and solar energy.

However, the CDM as a system crashed in 2012, with average prices moving from $10 per ton to pennies per ton, making most projects commercially unviable due various factors including the lack of high-emitting country commitments to targets set under the Kyoto Protocol. Nonetheless, projects continued to operate and issue credits with continued credit offtake arrangements until as recently as a few years ago. With the 2016 Paris Agreement and increase in corporate and country commitments around reaching net zero targets, there has been a revitalization of carbon markets globally. These types of markets are elaborated below.

Sources and/or additional resources:

Voluntary Carbon Markets

Voluntary Carbon Markets (VCM) allow carbon emitters to purchase carbon credits voluntarily to offset their emissions. Unlike compliance markets which limit the purchase of carbon credits and have jurisdictional restrictions, Voluntary Carbon Markets offer an opportunity for Africa-based carbon projects, which can be developed by private, public, and not-for-profit entities, to sell their carbon credits to global carbon credit buyers. The VCM is also an avenue for governments to attract foreign direct investments and achieve their climate mitigation goals. Currently, the VCM is one the most promising opportunities where carbon credits for Africa-based carbon projects are bought and sold.

Compliance Markets

Compliance markets regulate carbon reduction emissions by imposing legally binding emissions reduction targets on companies. They can be created at the industry level, whereby a governing industry body implements a framework for its member organizations to reduce emissions, such as the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA), or at the jurisdictional level, whereby a jurisdiction uses cap and trade schemes, known as Emission Trading Systems (ETS), or imposes carbon taxes.

While compliance markets are the largest type of carbon markets at ~US$100B annually, they primarily exist in industrialized economies such as Europe and California and allow very limited use of carbon credits to offset emissions. When they allow participants to use carbon credits, they have strict eligibility criteria that restrict geography of origin and project type, making compliance markets a limited opportunity for Africa-based projects today. South Korea and Singapore are the only two jurisdictions with compliance markets that accept carbon credits issued from projects in select African countries. South Africa is the only country on the African continent to have a compliance market.

In South Korea’s ETS, up to five percent of regulated emissions can be offset by carbon credits. Koko Networks, an alternative cooking fuels company based in Kenya, is already selling credits into the South Korean compliance market.

Singapore does not have an ETS but rather a carbon tax, which is currently set at US$5 per ton but will rise to US$80 per ton by 2030 to disincentivize emissions. The country is signing MOUs to develop bilateral agreements with countries such as Ghana, Sri Lanka, and Kenya from which it will allow eligible carbon credits to be used by Singaporean companies to offset up to five percent of their taxable emissions. As the carbon tax increases, demand for offsets from eligible countries is expected to rise considerably, which could present an opportunity for African carbon projects under the Singaporean compliance market.

In June 2019, South Africa’s Carbon Tax Act went into effect to help the country meet its climate commitments under the Paris Agreement. South African entities with carbon tax obligations can use carbon credits issued by government-recognized registries, such as Verra, to offset a portion of their tax liability.

Sources and/or additional resources:

Article 6

Article 6 of the Paris Agreement provides a mechanism for the trading of emissions reductions between countries (once traded, these reductions are known as “internationally traded mitigation outcomes” or ITMOs). In essence, countries that are not able to economically meet their NDCs can opt to purchase emissions reductions from other countries that have a lower marginal cost of abatement.

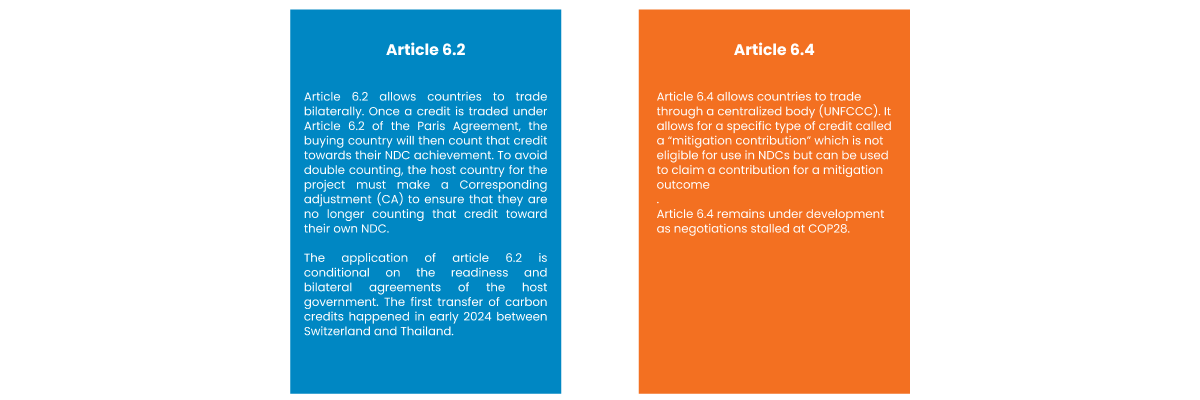

Article 6 of the Paris Agreement includes two market-based mechanisms for the international trade of carbon credits to support countries in achieving their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs):

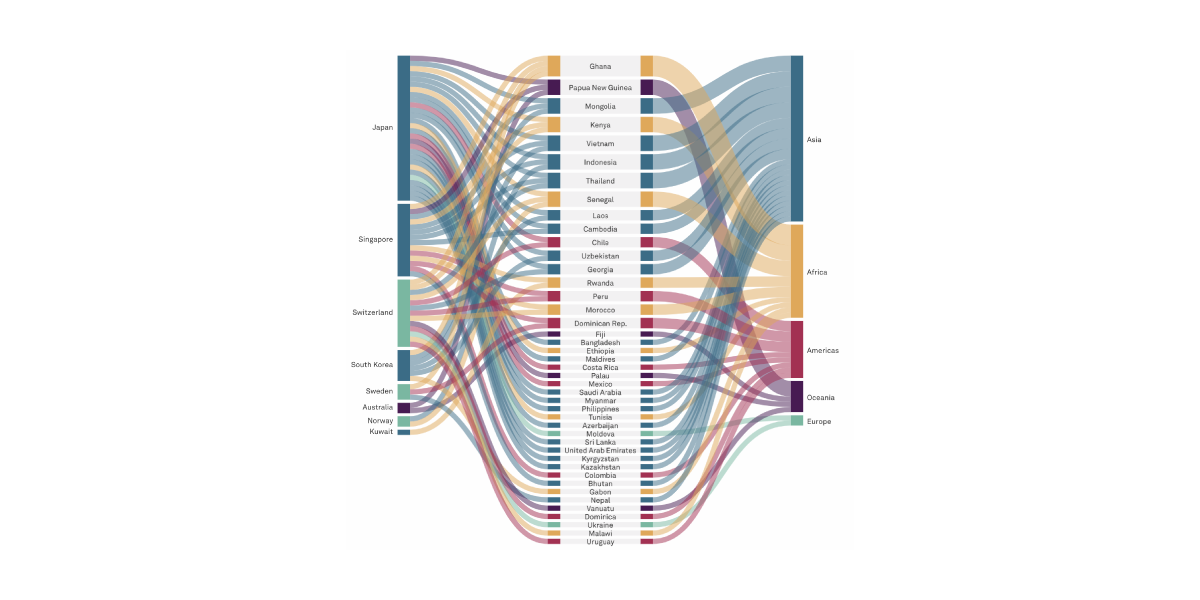

Article 6 creates a framework that allows countries to deploy capital or to require companies to deploy capital into carbon credit purchases, which can increase the amount of capital available to carbon projects in addition to compliance and voluntary markets. Approximately 69 bilateral agreements have been signed under Article 6, according to data compiled by S&P Global Commodity Insights and the UN Environment Programme. However, the framework remains in its early stage of development and the first deal to successfully close only concluded in January 2024 between Switzerland and Thai company Energy Absolute Public Co. Ltd. for the Bangkok E-Bus Program. Article 6 is also significant as it interacts with both compliance and voluntary markets and could affect the current regulations around carbon markets.

While Article 6 provides a promising source of funding, its frameworks of applications remain relatively nascent. Developers should follow the development of Article 6 globally and the issuance of new ITMOs under this mechanism, as well as the development of application framework by the country where they are developing their carbon projects.

Sources and/or additional resources:

"Not a complete list of project types that generate carbon credits."

Afforestation, Reforestation and Revegetation (ARR) refers to the restoration of terrestrial forest ecosystems, which has the highest climate mitigation potential in Africa.

The demand for ARR credits has been increasing, driven by the rising interest from carbon credit buyers seeking removal credits. Notably, the demand for ARR credits in Africa has increased, partly because they are traded at lower prices compared to ARR credits in developed markets.

Additional resources: A listing of ARR projects in Africa can be found on Berkeley Project's Voluntary Registry Offsets Database here (Includes VERRA, Gold Standard, Climate Action Reserve (CAR), and the American Carbon Registry (ACR)

Blue carbon refers to the carbon stored in coastal and marine ecosystems and is one of the nature-based solutions with the highest carbon sequestration potential.

Blue carbon projects refer to the protection and restoration of coastal and marine ecosystems including mangroves, seagrass meadows, and tidal marshes. However, blue carbon projects remain uncommon in Africa due to the high cost of development of their carbon credits.

Currently, mangroves are the most prevalent blue carbon projects. Other project types, such as seagrass, meadows, and tidal marshes remain rare, mainly because their corresponding methodologies are nascent and still under development by carbon standard setters.

Additional resources: Resources and tools on blue carbon can be found on Fair Carbon including a mapping of all Blue Carbon projects in Africa here.

Net farm emissions reductions (including soil carbon) refers to a basket of activities that can reduce net farm emissions (e.g. no till, reduced fertilizer use).

There is significant potential for net farm emissions in Africa, not only for climate mitigation potential but also for its impact potential on smallholder farmers. An increasing number of startups are working with smallholder farmers by using regenerative agriculture and MRV.

Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) refers to forest protection through the enhancement of enforcement capacity and/or incentivization of land steward behaviour. Historically, REDD+ has been the dominant project type within nature-based carbon projects in Africa.

However, since there is an increasing investor preference for carbon removal impact, REDD+ credits are currently trading at a lower price than removal projects. Carbon credit buyers are looking for improved baselining and Measuring, Reporting and Verification (MRV) in REDD+ projects to avoid issues of over-crediting.

Additional resources: We discuss price trends in section 2.2. A mapping of REDD+ projects globally including in Africa can be found on the UNFCCC REDD+ Web Platform

Improved forest management describes management techniques in commercial forestry, such as reducing harvest volumes which decrease emissions from forests, and lengthening forest rotation which remove and store carbon (IFM can either result in avoidance or removal of carbon).

Over 90% of the issued IFM credits are from North America, with only one project registered in Africa due to the limited availability of large-scale commercial forestry on the continent.

Direct Air Capture (DAC) technologies extract carbon directly from the atmosphere by using clean energy sources, such as renewable energy and energy-from-waste. Carbon can be permanently stored in deep geological formations or used for a variety of applications. Capturing carbon from the air is one of the most expensive carbon removal methods with costs ranging between US$250 and U$600.

Only 27 DAC plants have been commissioned worldwide to date. There is large potential for DAC in some parts of Africa due to the increasing availability of renewable energy sources; while DAC still currently as some of the highest costs per ton out of any carbon removal credits, DAC companies are looking to achieve significant cost downs to make it competitive to other durable CDR credits like biochar.

Additional resources: Information on DAC companies and other technology-enabled carbon removal projects globally can be found on CDR.FYI.

Biomass can be burned and converted into biochar, a form of permanent carbon removal. There is significant potential for biochar production in Africa, not only for climate mitigation potential but also for its impact potential on smallholder farmers.

Biochar has historically been difficult to scale on the continent given lower customer affordability. Carbon credits present an additional revenue stream that can enhance projects’ financial viability.

Additional resources: Information on biochar companies and other technology-enabled carbon removal projects globally can be found on CDR.FYI.

Enhanced rock weathering is a technology based on mineral-rock such as basalt that spreads rock dust as a form of permanent carbon removal. It has the potential to both sequester carbon in oceans and enhance soil quality.

Globally, ERW is still in its early stages, but there is high interest from some corporate credit buyers in this project type.

Through restoration and management of degraded land, biomass can be grown and buried for permanent carbon storage. While this can have interesting applicability in Africa, it is still nascent with only very few projects globally.

Clean cooking refers to the distribution and use of more efficient and/or alternative cookstoves, potentially with different fuels (e.g., ethanol, LPG), that can decrease deforestation and degradation from charcoal. Clean cookstoves are among the most prevalent credit-issuing projects in Africa, as there is a massive opportunity to convert households across Sub-Saharan Africa away from the use of charcoal.

Carbon credits have been used to reduce the price of cleaner cookstoves and fuels to improve the affordability of these products for households. Carbon credit buyers are looking for improved Measuring, Reporting and Verification (MRV) to avoid quality issues such as over-crediting.

Additional resources: A listing of improved cookstoves projects in Africa can be found on Berkeley Project's Voluntary Registry Offsets Database here (Includes VERRA, Gold Standard, Climate Action Reserve (CAR), and the American Carbon Registry (ACR)

Large scale renewable energy refers to sources such as solar, hydropower, and wind. Carbon credit issuing renewable energy projects represent the highest number of credit issuing projects in Africa, but remain limited compared to other regions, such as Asia.

Rules around renewable energy carbon credits have tightened due to the difficulty of proving additionality and establishing a baseline, particularly when a project is not replacing a polluting energy source. We discuss additionality and project baseline in section 2.4.

Additional resources: A listing of renewable energy projects in Africa can be found on Berkeley Project's Voluntary Registry Offsets Database here (Includes VERRA, Gold Standard, Climate Action Reserve (CAR), and the American Carbon Registry (ACR)

Clean water solutions such as the distribution and use of water filtration systems present a cleaner alternative to the use of firewood or charcoal for boiling water. Similar to the case of improved cookstoves, carbon credits have been used to reduce the price of water filters to make them more affordable to low-income households. There are ~300 clean water projects in Africa and a number of projects combines water filtration systems with improved cookstoves.

Additional resources: A listing of clean water and community borehole projects in Africa can be found on Berkeley Project's Voluntary Registry Offsets Database here (Includes VERRA, Gold Standard, Climate Action Reserve (CAR), and the American Carbon Registry (ACR)

Waste management projects include various types of handling waste in ways to minimize its environmental impact. They include food waste management, landfill gas combustion and biogas to energy projects. There are 25+ waste management credit issuing projects in Africa, most are in composting and landfill methane.

Additional resources: A listing of waste management projects in Africa can be found on Berkeley Project's Voluntary Registry Offsets Database here (Includes VERRA, Gold Standard, Climate Action Reserve (CAR), and the American Carbon Registry (ACR)

Off-grid solutions encompass solutions that give access to clean energy, such as mini-grids, or allow conversion from polluting sources, such as solar irrigation that replaces diesel pumps. Carbon credits present an additional revenue stream that can enhance projects’ financial viability as the cost of production of these solutions is high relative to their customers’ willingness to pay. However, like renewable energy, establishing a baseline and proving additionality. We discuss additionality and project baseline in section 2.4.

Sources and/or additional resources:

The global Voluntary markets reached US$2B in 2022, primarily driven by Asia (US$765M) and Latin American & Caribbean (US$506M), followed by Africa (US$164M) and North America (US$136M). The Task Force for Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets estimates that voluntary carbon markets need to grow by >15x by 2030. Globally, forestry and land uses’ carbon credits represent majority (>40%) of all credits issued.

Key growth drivers of voluntary carbon markets include the increasing number of corporate net zero commitments, an increased government activity to engage with voluntary carbon markets, and the development of the enabling environment, namely independent standardization bodies, such as VCMI, ICVCM and SBTi.

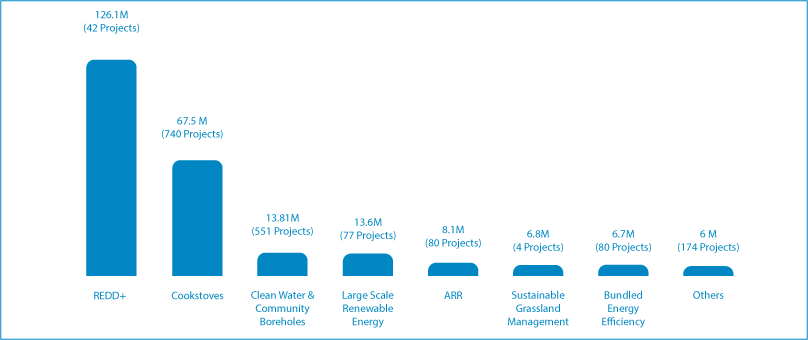

The VCM market in Africa remains nascent relative to other regions, and ACMI’s ambition is to unlock US$6B in revenue from the VCM in Africa by 2030. Currently, most credits issued in Africa are from REDD+, cookstoves, clean water & community boreholes, large scale renewable energy, and ARR

Sources and/or additional resources:

According to Climate Focus’ VCM Primer, the “price for a carbon credit is an essential piece of information for both the supply and demand side of the market. On the demand side, buyers benchmark the costs of meeting corporate climate targets against the carbon price to determine what role the VCM can play in achieving those targets. On the supply side, clear price signals are important for developers to decide whether it is worth developing VCM activities and how much carbon finance can contribute to development and implementation costs.”

Carbon pricing this past year

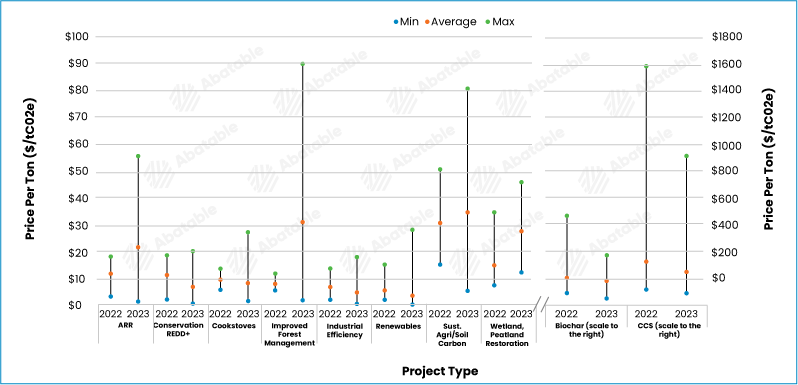

Based on Abatable analysis, most nature-based carbon credits (ARR, IFM, Soil Carbon, Blue Carbon) were traded at higher prices on average in 2023 than in 2022, but prices in 2023 varied across a greater range.

All other credit types, including REDD+, saw a decline in price in 2023 compared to 2022. This is due to many factors. First, many of the credits that are currently being traded are from older vintage and are perceived as lower integrity since requirements on carbon credits were less stringent in the past. Second, media scrutiny of projects has suppressed demand as buyers are becoming more cautious and waiting to see how the space develops before making new purchases. Third, the macroeconomic environment of the last year has seen the highest inflation in decades, putting pressure on non-essential corporate spending. This decline has occurred even as more corporates make net-zero commitments, which will help drive future demand for carbon credits.

Nature-based carbon removal credits traded at a premium relative to nature-based avoided emissions credits. This is because removal credits are currently perceived as higher integrity, which has been driving demand from buyers relative to their supply. As such, nature restoration traded at a higher price than other credit types in 2023. For instance, ARR traded at ~US$22/ton and blue carbon (wetland, peatland restoration) traded at ~US$28/ton on average.

Negative press around REDD+ projects including additionality (discussed in section 2.4), bad practices, and issues of fair payments to local communities, has been dampening demand from buyers. The lower demand relative to the high supply of REDD+ projects resulted in REDD+ credits trading at less than US$10/ton on average. Successful projects showing high quality and high integrity can counter the negative narrative and repave the way for higher demand at higher prices for REDD+.

Renewable energy credits are the cheapest, given the high supply of these credits but lower market demand due to mixed views on the additionality of some renewable energy projects. As renewable energy becomes the default alternative, there is a question on whether carbon credits are required to make it financially competitive to fossil fuel-driven energy. In 2023, Renewable Energy credits traded at lower than US$5/ton on average.

While cookstove credits present a big opportunity to transition cooking away from charcoal at scale in Africa, cookstove credit prices trade at lower prices due to negative press around the accuracy projected and actual impact. In 2023, cookstove credits traded at lower than US$10/ton on average.

Carbon pricing projections

Several organizations produce future carbon pricing estimates, with organizations such as Trove, BloombergNEF (BNEF), and McKinsey & Company on the more conservative end (US$50-80/tCO2e by 2050), and the likes of EY and Credit Suisse on the more bullish end (US$150-200+/tCO2e by 2050).

These future price projections are based on a combination of current pricing and future demand and supply, which are in turn based on different scenarios in government regulation, corporate action and buyers’ preferences for specific credit types relative to other types, and unit supply cost for project types relative to others.

Trove’s and BNEF’s full 30-year pricing projections are commonly used and considered by some as more conservative, offering a more defensible base-case scenario. However, any future price projection must be carefully tailored given the potentially wide price discrepancy based on individual project characteristics. A scenario analysis on future pricing is recommended when developing the financial projections of a carbon project. This provides a practical perspective on the project’s financial viability, guides the design of co-benefits, and informs the fundraising size and negotiations with investors.

Sources and/or additional resources:

A project proponent is the entity that obtains the rights to the carbon credits from the owners of the physical carbon.

A project developer is the entity responsible for the design and development of the carbon project.

Particularly relevant to Agriculture, Forestry, and Other Land Use (AFOLU) activities, many communities own, have customary access, or manage land where projects are taking place. Also referred to as Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPLCs), IPLCs should play an integral and central role in the design and implementation of carbon projects and should receive their fair and equitable share of co-benefits.

Carbon standards setters (“Standard Setters”) are essential to promote industry self-regulation and the development of the VCM, Standard Setters set the requirements that carbon project activities must fulfill to generate tradable carbon credits. Standard Setters develop methodologies, which aim to quantify the real impact of projects on GHG emissions and largely depend on project type. These methodologies provide various requirements and procedures, such as guidelines on how to identify the project baseline and assess additionality against the identified baseline. Standards assess projects according to the requirements of these methodologies to approve project registration and issuance of credits or Verified Carbon Units (VCUs). Registries are a part of Standard Setters and have the responsibility to centralize data related to project validation and verification, and to report and track ownership, trade, and retirement of carbon credits.

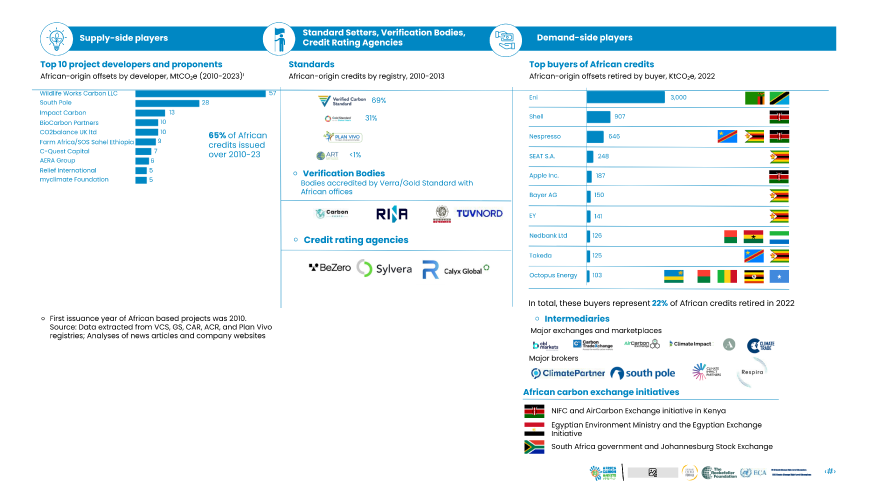

Verification and Validation Bodies (VVBs) are independent third-party auditors who are approved by Carbon standard bodies. As defined by VERRA, VVBs determine whether a project meets the requirements set by the Standards during the project validation. During the project verification stage, VVBs verify whether a project achieved and quantified the outcomes set out in the project documentation according to the requirements of the Standards. There are almost no local validation/verification bodies (VVBs) in Africa.

Carbon Credit Agencies are third-party organizations that issue ratings to credits produced by specific projects, which rate the projects’ likelihood to deliver real carbon impact. Carbon Credit Agencies were created in response to a rising demand from credit buyers for quality markers beyond common industry standards. Carbon Credit Agencies rate credits globally including in Africa.

Buyers (or end buyers) of carbon credits are companies looking to offset some of their carbon emissions. These players are also known as credit offtakers. Some of these credit offtakers (including buyers) may also provide financing upfront in return for credits later, which is usually referred to as pre-financing or a pre-purchase agreement. For an expanded mapping of buyers, please refer to the Introduction to Carbon Finance webpage.

Intermediaries are buyers or brokers of carbon credits that aim to on-sell to other intermediaries or end-buyers. They either purchase and resell the credits or charge a fee on the value of the credits sold. Some may also be online marketplaces.

Country governments (including at the local and national level) play a critical role in regulating the development of carbon projects, taxation on carbon revenues, and carbon credit trading.

Funders provide financing to carbon projects from private or public sources. For an expanded presentation of financial instruments for carbon projects, please refer to the Introduction to Carbon Finance webpage

MRV providers are organizations that help projects conduct ongoing Monitoring, Reporting and Verification (MRV). There are dozens of growing start-ups that are building digital MRV platforms (dMRV) which leverage technology to enable and decrease the cost of conducting MRV at scale. MRV companies generally have a specific sector or approach of focus (e.g. agriculture, soil carbon, biodiversity).

Sources and/or additional resources:

Developing high-quality, high-integrity projects is imperative from an ethical standpoint, particularly where it pertains to benefits shared with the communities. In addition, there is an increasing demand for high-quality and high-integrity projects by credit buyers, partially because association with a low-quality or fraudulent project can be damaging to the buyers’ reputation. This is particularly relevant because African carbon markets faced negative press surrounding projects that were over-credited or engaged in harmful practices. A high-quality high-integrity project not only attracts more buyers but also enhances the credibility of the entire market, encouraging further investments in African carbon markets.

There are several industry-level initiatives to set clearer guidelines on integrity for both sellers and buyers of credits, including:

The Voluntary Carbon Markets Initiative (VCMI) is a global governing body aiming to build a high-integrity VCM by ensuring that corporate claims are not at risk of greenwashing.

The Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market (ICVCM) is another governing body setting benchmarks for the integrity of carbon projects. Through their Core Carbon Principles and its associated assessment framework, projects and methodologies will be able to become “CCP-eligible”. CCP-eligible projects and methodologies mean they meet a high standard of disclosure and integrity. The CCPs were launched in the second half of 2023 and intended to be the go-to benchmark as more projects and methodologies are evaluated.

Components that indicate quality and integrity include additionality, non-leakage, permanence, conservative baselining, co-benefits, and Monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV). In addition, it is important to establish strong safeguards, which are the set of policies and practices that ensure and maintain projects’ environmental sustainability and social responsibility.

Regulations around carbon markets are still evolving and project developers should understand local laws and follow closely their evolution since regulations are often changing.

Key regulations to monitor are:

Applications of Article 6 and Corresponding Adjustments: Countries are in various stages of developing the regulatory framework for applying Article 6, so carbon project developers need to follow the evolution of local frameworks in the project’s host country closely. Article 6 stipulates that once a credit is sold, the host country of the project must take a Corresponding Adjustment (CA) to ensure that the country is not double counting that credit by counting it toward their own NDC. There is currently no mechanism or infrastructure for issuing and tracking correspondingly adjusted credits within the voluntary markets. However, there is a growing perception among investors, brokers, and buyers that these types of credits are a marker of quality, or that they may serve as protection against potential expropriation of credits from the host government, which could otherwise claim right over the carbon credit towards its NDCs or sell as their own ITMOs.

Land tenure: Particularly relevant to AFOLU sectors, it is essential to understand and assess local regulations around land tenure and their implications on carbon rights to evaluate the feasibility of the carbon project in a given country. In many parts of Africa this is made more complex by customary rights communities may have over land. Securing land tenure (whether through buying land or signing agreements with landowners, which may be customary land rights holders) requires sufficient lead time and is usually a lengthy process.

Carbon taxes: Governments can impose or increase taxes on the revenues generated by carbon projects, which can impact project returns (alternatively governments may lay claim to a portion of credits). A scenario analysis on taxes is recommended when developing the financial projects of a carbon project to help assess the financial impact in the case of such scenario.

Sources and/or additional resources:

Agriculture, Forestry, and Other Land Use (AFOLU): A sector classification that includes activities related to agriculture, forestry, and land use, often targeted for emission reduction and carbon sequestration efforts.

Carbon Standard Setter: An organization that establishes and oversees standards for the creation, verification, and trading of carbon credits in carbon markets.

Clean Development Mechanism (CDM): Defined in Article 12 of the Kyoto Protocol, a CDM allows a country with an emission-reduction or emission-limitation commitment under the Kyoto Protocol to implement an emission-reduction project in developing countries.

Climate adaptation: According to the European Environment Agency, climate adaptation refers to “anticipating the adverse effects of climate change and taking appropriate action to prevent or minimize the damage”.

Climate mitigation: According to the European Environment Agency, climate adaptation refers to “making the impacts of climate change less severe by preventing or reducing the emission of greenhouse gases (GHG) into the atmosphere”.

Carbon Credit Issuance: The process of officially creating and distributing carbon credits, typically following the verification and validation of emission reduction activities.

Carbon Credit Retirement: The permanent removal of carbon credits from circulation, indicating that the corresponding emission reductions have been accounted for and the credits are no longer available for trading.

Carbon Credit Vintage: The specific year in which carbon credit is issued, reflecting the vintage's environmental attributes and the emission reduction methodologies applicable at that time.

Concessional Capital: Funding provided at favorable terms, such as low-interest rates or extended repayment periods, to support projects that have positive environmental or social impacts.

CORSIA (Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation): A compliance market for the aviation industry, focusing on offsetting and reducing carbon emissions.

GHG Emissions: Greenhouse Gas Emissions. The total amount of greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide and methane, released into the atmosphere by human activities.

High-Integrity Carbon Project: A carbon offset project that adheres to rigorous standards and practices, ensuring the credibility and reliability of the emission reductions claimed.

High-Quality Carbon Project: A carbon offset project that meets stringent criteria for environmental and social co-benefits, in addition to verifiable emission reductions.

ICVCM (Integrity Council for Voluntary Carbon Markets): developed the Core Carbon Principles (CCPs) and Assessment Framework (AF) that will set new threshold standards for high-quality carbon credits. ICVCM provides guidance on how to apply the CCPs, and defines which carbon-crediting programs and methodology types are CCP-eligible.

ITMOs (Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes): represent emission reductions or removals that can be transferred between countries under Article 6.

Methodology: A set of rules and procedures defining how emission reductions or removals are quantified and verified in a carbon offset project.

MRV (Measurement, Reporting, and Verification): refers to measuring the amount of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reduced by a specific mitigation activity

Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs): Commitments made by countries under the Paris Agreement, outlining their climate action plans and targets to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Net Zero Targets: net zero targets are commitments, often set by corporations, to have a net zero impact on climate. According to the United Nations Climate Action, net zero means cutting greenhouse gas emissions to as close to zero as possible, with any remaining emissions re-absorbed from the atmosphere, by oceans and forests for instance.

Over-crediting: Refers to the issuance of a number of carbon credits that exceed their equivalent of emission reductions.

Project Baseline: The reference scenario against which emission reductions or removals are measured in a carbon offset project.

Regenerative agriculture: the process of restoring degraded soils using practices based on ecological principles.

SBTi (Science-Based Targets initiative): defines and promotes best practice in science-based target setting offering target-setting resources and guidance, which are assessed independently by SBTi

The Task Force for Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets: A global initiative focused on developing and implementing standards for voluntary carbon markets to enhance transparency and credibility.

VCMI (Voluntary Carbon Market Integrity Initiative): develops high integrity guidance (VCMI Code of Claims) for buyers of carbon credits, including on climate claims by businesses, supports access to high integrity voluntary carbon markets, and monitors broader supply-side integrity efforts.

Verified Carbon Units (VCUs): Carbon credits that have undergone a third-party validation and verification process to ensure their legitimacy and accuracy.